During the conversation I was lucky enough to host with Tim Crouch the other weekend, there was a question from the audience about care in his shows. Particularly with a show like The Author, which made the audience disturbingly complicit in the violence and abuse it described, the idea of care becomes crucial. Tim replied that it’s about a relationship of openness with an audience, about inviting them into a contract. That, perhaps, is why it was so important for audiences in that show to know that they could leave, that part of that contract was the option to walk out and refuse to be complicit.

I was reminded of a (rich and brilliant) conversation I listened to about a year ago between Alex Swift and Chris Goode, which also grappled with this notion of caring for an audience within a piece of theatre and what that really means. It also reminded me of Fake It ‘Til You Make It, the show Bryony Kimmings has made with her partner Tim Grayburn, which I’d seen at Soho Theatre just a few days earlier. In that show, care is everything. There’s the very visible care that Bryony and Tim take of one another on stage throughout the show, there in little looks and fleeting touches, but also the care they show towards their audience. This is their story, but they’re telling it for us.

Like Bryony’s last show, the brilliantly galvanising Credible Likeable Superstar Role Model, Fake It ‘Til You Make It is a potent blend of autobiography and activism. Also like that show, made with Bryony’s young niece Taylor, this new piece features a non-professional performer in the shape of Tim. And just as Taylor was the catalyst for Credible Likeable, it’s Tim and his experience of clinical depression that form the starting point for Fake It ‘Til You Make It, opening out into a wider look at men and mental health. The personal is always political.

Care starts with the tone. After a gloriously silly opening dance, Bryony steps up to the microphone to explain to us what’s happening here – to set out the contract. “This is a love story,” she warns us. “I know. Gross.” She elaborates: this is a story about men with clinical depression (like Tim) and the women who love them (like Bryony). It’s going to get dark, Bryony admits. But she also wants to look after us, hence the good luck dolls scattered around the stage and the purposeful silliness of the aesthetic. Sometimes, the only way to seriousness is through humour.

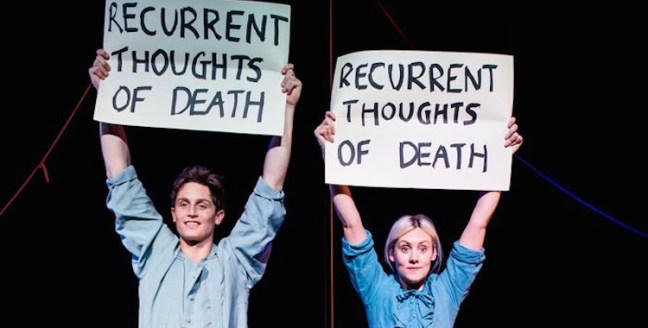

And every silly touch is there for a reason. Tim’s face is kept covered by ridiculous headgear – binoculars, paper bag, fluffy cotton-wool clouds – because one of his conditions for appearing on stage was that he wouldn’t have to look at the audience. When he comes out with a tangle of ropes atop his shoulders, this initially whimsical device has transformed into a simple but affecting metaphor for Tim’s mental turmoil, making it all the more emotional when he is finally revealed to us and speaks, exposed, directly to the audience.

The love story itself is also silly in the telling, cute and self-mocking in equal measure. Bryony and Tim collide, literally and metaphorically, their lives unexpectedly smashing into each other. Their early romance is almost childlike in its sweetness, played out in cartoonish smiles and dorky dance moves, and when the couple move in together they drape a tent across the stage like a kids’ den. When Bryony discovers Tim’s anti-depressants, then, it’s with a rude jolt. The illness that he has kept secret for years disrupts the bliss of their shared life, injecting the romance with darkness but also with honesty.

Honesty – always startling, sometimes embarrassing – is a recurring trait of Bryony’s work and right at the heart of what she’s doing here. What is as damaging as the depression itself for Tim and other men like him is the shame that has needlessly become attached to it. When he does eventually speak to us, Tim confesses one of his greatest fears: that suffering from mental health issues would somehow make him less of a man. There’s a tangible release in banishing that shame, in forcing it out with frankness.

In lots of ways it’s also an illustration of the same blunt but necessary point I made in writing about Violence and Son: patriarchy shits on everyone. Masculinity is oppressive to men as well as to women, its demands to “toughen up” and “grow a pair” stifling the possibility for many men to even acknowledge their feelings, let alone talk about them. Having seen this social pressure inflict its scars on men in my own life, the bold openness of Fake It ‘Til You Make It is a deep sigh of relief.

That’s not to say that Fake It ‘Til You Make It can’t also be difficult. When I saw an early scratch of the show, at Forest Fringe in Edinburgh last summer, I was an emotional mess by the end. Returning to it over a year later (and minus the deadly cocktail of stress and sleep deprivation), I found it less tear-jerking, but there are still some really black moments. When Bryony searches blindly through the streets of London for a floundering Tim, it’s painful to watch, like an icy fist grasping through the ribs, and the more exposing moments of the performance feel just as raw as in that charged room in Leith last year. Talking about reality or truth on stage is always problematic, but when Bryony and Tim laugh and cry together it’s real laughter, real tears.

It’s important, then, for our laughter and tears – our presence in the room with them – to also be acknowledged. Fake It ‘Til You Make It cares for its audience by never pretending that we’re not there and always keeping our responses in mind, right up to the invitation to speak to or email Bryony and Tim after the show itself has finished. In many ways, the piece they have created is one long, generous act of making visible – and that includes us.

Photo: Richard Davenport.