Originally written for The Stage.

Paul Barritt, animator and co-artistic director of theatre company 1927, is frank about the challenges of using projection onstage. “Ask anyone who’s worked with video in theatre and they will say that it is a nightmare,” he says. It’s perhaps surprising, then, that video has remained such an integral ingredient in 1927’s work ever since its Edinburgh Fringe breakthrough with Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea in 2007. As Barritt puts it: “It’s core to the very idea of what we do.”

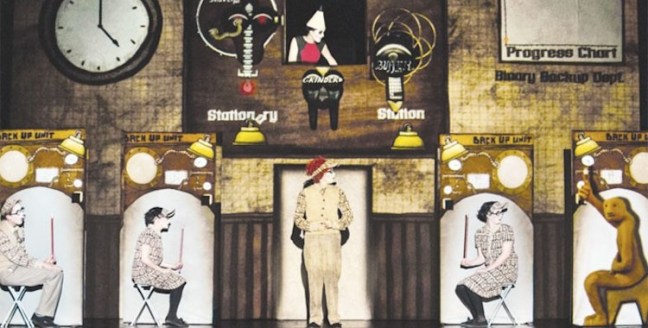

Live performance is put in front of an animated backdrop in 1927’s shows, using projections in novel and surprising ways. The two-dimensional and three-dimensional layer on top of one another form one unique texture. Their debut, Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea, drew on silent film techniques to integrate a monochrome film with performers on stage, while hit show The Animals and Children Took to the Streets exploded the same technique into vibrant colour.

The key to 1927’s successful use of projected animations, providing the company’s distinctive style, is collab-oration. “It’s never really just me sitting there making my own animations,” says Barritt. “It’s a very collaborative way of working, and that’s the only way that it really works.”

Barritt offers the example of Golem, which the company is currently taking on tour after its premiere last year at the Young Vic. The show draws on the centuries-old myth of the golem, drawn from Jewish folklore, to create a satire of 21st-century capitalism and technology, with the clay servant of the title fast becoming a must-have, life-ruling accessory. The concept came jointly from Barritt and fellow artistic director Suzanne Andrade, who worked together from the very beginning on both the ideas and aesthetics of the show.

“We knew we wanted to set it in a city and we knew that part of the journey was going to be going from a chaotic, exciting metropolis into this homogenised, Westfield-type city,” Barritt explains. “Aesthetically, we talked about lots of different things.” Inspired by the “hodgepodge” quality of downtown Los Angeles, the city has a collage quality that then flattens out into an “almost pop art aesthetic” as the world of the show becomes increasingly neat and uniform.

The company’s shows are known and celebrated for their almost seamless integration between animation and performances, making an often clunky marriage of live and filmed elements appear effortless. Barritt tells me that this, too, comes from that close collaboration on the overall aesthetic of the show, which extends to performance style.

“Suzanne’s style of direction is very much focused towards bringing out the best in the animation,” he says. “You have to make the actors as large as the animation and they have to behave a bit like the animation behaves, so they have to act in a very gestural way and it has to be slightly heightened because we’re in a big, illustrated, heightened world.”

And it’s not just the performances that have to marry up with the images. Music is also essential to 1927’s shows and helps to hold all the other elements together. “Everything’s timed to the music,” Barritt explains. “It’s when you’ve got this synchronicity of everything, that’s what makes it all work.”

Although the animated worlds that Barritt creates for 1927’s shows would seem to have much in common with film, he warns that “you can’t go too cinema-tographic on it”. He continues: “The film elements that I’m making, I’m doing them in a very theatrical way and they’re actually much more like moveable, animated bits of set than they are film. For example, we’ve never really been able to do close-ups, we’ve never worked out how to do close-ups properly or in a good way. You can’t do it, because your actors are there on stage and it’s all to do with the scale.”

While this means limitations, Barritt sees such constraints as creative rather than frustrating. “You might start off with an idea and it’s this giant thing, this massive idea that you’ve had, but the actual logistics force it into becoming something different and often something better,” he suggests. “Limitations are really good things to work within; it’s much better to have them.”

The process has, however, got easier over the years, both as 1927 has increased in reputation and capacity and as the technology it is working with has improved. After starting out working with DVDs – which Barritt says are now “virtually obsolete” – the company has more recently begun working with a media server that allows Barritt to break the show’s animations down into individual chunks.

“All the animated events are cued,” he says, “so this has made it easier for timing purposes and it has also made it easier to reshape the film. We used to use just one film that played through, so if there was one tiny element in the film that didn’t work, I’d have to go into one massive film and just change one element, and then that can throw a spanner in the works.” He adds that the media server “loosens things up”, allowing more flexibility both in rehearsal and in performance.

New, more sophisticated technology has also eased the often painful process of transferring the company’s shows from venue to venue.

“With the media server it’s much better,” says Barritt, though he admits that there can still be problems. “Every projector is different: it’s really one of the more imprecise technological arts, setting up a projector, because each distance on each angle is always different and that affects how the projection is on the screen.”

Apart from moving to a media server, Barritt insists that technological developments have altered very little about 1927’s ways of working over the past eight years. “The way we’re using [the technology] is quite simplistic, really, in comparison with how some people use it,” he says. “The essential nature of what we’re doing hasn’t changed since we were using DVDs. Our actual process hasn’t really changed according to the technology at all. There are hundreds of things you can do with the technology, but that doesn’t mean you should do them.”

While the technology now allows the likes of motion sensor triggering and live feeds, 1927 hasn’t yet been tempted by such tricks. “People can get seduced by technology a bit and use it just because they can, which is ridiculous”. He says that 1927, on the other hand, would “only use it if we really thought the idea warranted it”.

For now, though, the company is happy to continue within the niche it has carved out for itself. “I think our process is still giving,” says Barritt, “and we’re still finding new ways of doing stuff within it.” The company is unlikely to be doing Shakespeare or kitchen-sink realism any time soon, Barritt adds, but that’s not where its interests lie.

“We’re ploughing our furrow and we’re quite excited about it still,” he says.

Photo: Bernhard Muller.