Originally written for Exeunt.

When is the right time to speak up? That’s one of the questions lurking amidst the chaos and clutter of Told by an Idiot’s latest show, which tells the story of one person – Thomas Aikenhead – who spoke up at precisely the wrong time. Or at least that’s one way of looking at it. Was this obscure, unlikely hero a champion of free speech, or just a kid who didn’t know when to shut his mouth?

Hearing the name Thomas Aikenhead, audiences might well ask – in the words of one of the show’s many songs – “who the fuck is he?” A footnote in British history, Aikenhead was the last person to be executed for blasphemy in this country in 1697. Just 20 when he died, he was a curious and opinionated student who fell foul of higher powers and paranoias – in particular, those of James Stewart, Lord Advocate of Scotland, who made an example of the hapless Aikenhead.

Of course, this is Told by an Idiot, so it’s no straightforward telling. The company bring their characteristic dark humour and lovable silliness to Aikenhead’s tale, as well as a collection of tunes penned by Iain Johnstone and Simon Armitage. The result is Brecht/Weill musical theatre meets the broad, belly-laughing comedy of the music hall (rather appropriately for the gorgeous surroundings of Wilton’s). There’s also an attempt to highlight the present day resonance of Aikenhead’s fate, putting the game eight-strong company in a dressing-up-box hodge-podge of period and modern costume and framing the central story with a group of Edinburgh officials squabbling over who to commemorate with a new statue in the city.

The narrative, meanwhile, is shot through with glimpses of others who were at odds with or ahead of their time: a Bowie T-shirt, a Sex Pistols record, an Einstein dream sequence. Whether Told by an Idiot are lobbying for a place for Aikenhead in the same line-up, however, is unclear. When he sings with passion and lyricism about the importance of the truth, he becomes a beacon of rationalism and progress. But then elsewhere it’s his ordinariness that’s underlined. Like any inquisitive and gobby student, he’s just trying to make his mark in whatever way he can.

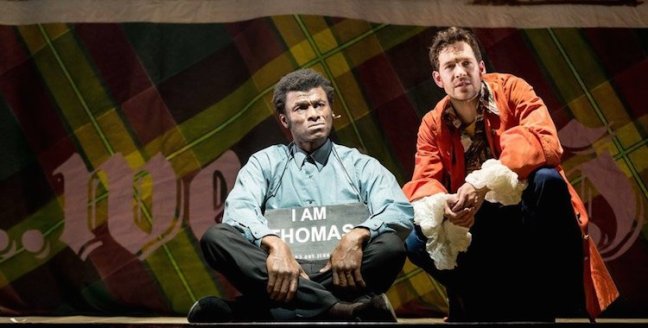

Told by an Idiot seem, at times, to be having their cake and eating it. Take the title, emblazoned across pieces of clothing worn by various members of the cast. The role of Thomas is thus passed around, never resting for too long on any one person’s shoulders. The message is twofold. On the one hand, any of us could be Thomas, an ordinary young man who was just in the wrong place at the wrong time. He’s nothing special. On the other hand, though, “I Am Thomas” is just one step away from “Je suis Charlie” (and barely half a step away at one pointed moment in the show), turning this unlucky, outspoken student into a tragic symbol of free speech.

The show’s aesthetic is no less busy and contradictory. At some moments, it’s a political thriller, with the church’s spies lurking in dark corners clad in trench coats and shades. At others, it becomes a game, commentated on by two Match of the Day pundits (“nice move there from Stewart”; “that’s definitely a yellow card offence”). Pop cultural references are everywhere, from comic-book backdrops to snippets of dialogue from Jaws and The Life of Brian. There is, in other words, a lot going on. Too much, I begin to think. However brilliantly performed by the cast, whose energy doesn’t let up for a moment, the sheer quantity of different skits can become distracting, garnishing rather than actually telling Aikenhead’s tale.

Perhaps, though, it’s right that Told by an Idiot don’t close down this story; that they don’t make it definitively either a celebration of free speech or a simple tale of misfortune. Like the potential statue bickered over by the Edinburgh councillors, figures such as Aikenhead mean different things to different people. He’s available as a symbol of the pursuit of truth and equally as an example of foolishness, just as Stewart can be seen as a great reformer or a bullying authoritarian. Who the fuck is Thomas Aikenhead? Whoever you want him to be.

Photo: Manuel Harlan.