Originally written for the Guardian.

Captioned and signed performances have become common in theatre, with BSL interpreters and LED displays a familiar presence at the side of the stage. But theatres are increasingly making their work accessible for deaf and disabled audiences in a more creative, integrated fashion and are placing issues of access right at the heart of their design.

Graeae theatre company’s touring production of Jack Thorne’s play The Solid Life of Sugar Water, which arrives at the National Theatre in London this week, imaginatively incorporates live captioning at all of its performances. Birmingham Rep, meanwhile, is preparing to open a new version of Nikolai Gogol’s The Government Inspector with an integrated cast of deaf, disabled and able-bodied performers. Rather than being hidden away, the latter show’s audio describer and sign language interpreters will be incorporated as characters within the world of the play and have been involved in the production right from the start.

Roxana Silbert, artistic director of Birmingham Rep, is enthusiastic about the ways in which creative access can open up aspects of Gogol’s play. “Sign language is great for The Government Inspector,” she says, “because there are a lot of secrets and lies in the play and a lot of people who are saying things that other people don’t understand. So having that second language enhances what the play is already trying to do.”

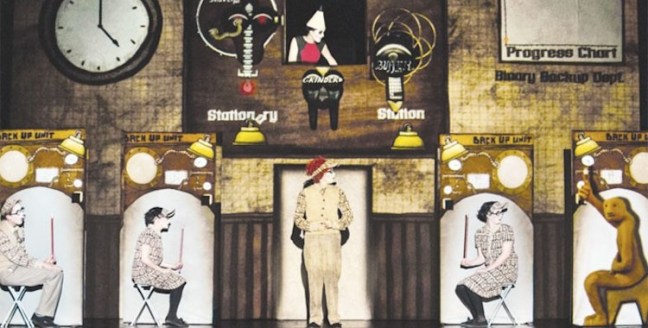

The show’s aesthetic has been affected in more subtle ways by the access needs of its performers. “Once you start looking at it from the actors’ point of view and what they need to make the stage work for them, actually what it does is make the stage a really interesting place,” Silbert says. The set for The Government Inspector suggests the lobby of a hotel, with various levels accessed by ramps and a lift as well as stairways and ladders.

Graeae has championed disabled artists and accessibility since it was founded in 1980. Those decades of work are now informing new initiatives aimed at improving access and widening opportunities for disabled artists across the sector. One of these is Ramps on the Moon, a collaborative network of theatres being funded by Arts Council England and supported by Graeae to create three new pieces of touring theatre that put disabled artists and audiences at their heart. The Government Inspector is the first of these.

Graeae’s Amit Sharma, the director of The Solid Life of Sugar Water, is also interested in how access can be incorporated in ways that speak to the themes of the piece. Thorne’s play tells the story of a couple attempting to overcome grief and regain intimacy. The whole show is set in the protagonists’ bedroom and takes an incredibly candid approach to relationships, sex and the difficulty of communication.

“Because of the nature of the text and it being very explicit in how it’s describing certain sexual acts, I made the decision very early on of not using British Sign Language,” says Sharma. Instead, captions are projected on to the bed that the two characters share, which the audience see as if from above. “When we were working with the set and the elements of access … we always said there are three characters in the play: there are the actors and there’s the bedroom,” he says, stressing the importance of the design. The prominence of the captioning in this intimate shared space highlights the play’s themes of communication – and lack of it. As Sharma puts it, “to have those words spelt out gives it an extra meaning, an extra layer”.

Within the play, references to the specific disabilities of the performers are incidental rather than integral. “We just went for the actors who felt right for the roles,” says Sharma. After Genevieve Barr and Arthur Hughes had been cast, Thorne made small changes to the script to refer in passing to Barr’s deafness and Hughes’s arm impairment – details that are always secondary within the narrative. “Disability is irrelevant,” Sharma says. “It’s the story that matters.”

The Solid Life of Sugar Water was staged at the Edinburgh festival last summer where it was one of many shows representing a game-changing year for disabled artists at the fringe. It prompted audiences and theatre-makers to think about accessibility in different ways. This kind of work, however, requires support. In addition to the backing of the Arts Council, which has awarded £2.3 million of funding to Ramps on the Moon, Silbert stresses the importance of safeguarding schemes such asAccess to Work. “It is about performers who have specific requirements being able to get the Access to Work support they need,” she says. “That’s where the problem is going to lie, not in theatre funding.”

Photo: Patrick Baldwin