Originally written for The Guardian.

It’s hard to imagine a more complete depiction of a relationship than the one that Danny Braverman unearthed in a dusty shoebox five years ago. Laid down over almost 60 years, the 2,500 or so images were the work of Braverman’s great uncle Ab Solomons, a shoemaker who started scribbling pictures for his wife, Celie, on the back of his weekly wage packets in 1926.

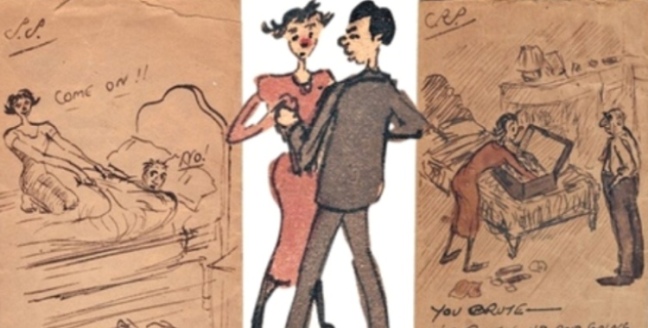

Beginning in London’s East End, where Ab worked and lived, the drawings trace the evolution of a marriage, as flirtation gives way to bickering and domestic contentment is ruptured by painful events. There are bedroom scenes where Ab jokes about his snoring; and others where the quarreling couple are locked in stalemate. One is annotated with the telling words, “I can be as obstinate as you can.” We see the growth of Ab and Celie’s two sons, and the growing spectre of illness. Celie is a constant presence, pictured forever as she was when the pair married.

There is an extraordinary honesty in Ab’s refusal to skip over the agonising episodes in his life with Celie. “These aren’t cartoons; this isn’t being funny,” Braverman says. “As an artist, he had a compulsion to tell the truth.”

“I challenge anyone to find a more comprehensive picture of one person by another person,” agrees Nick Philippou, the director who helped Braverman bring Ab and Celie’s story to the stage. “It’s so vast and so relentless.”

Flickering away in the background is the social history of the 20th century, from blitz to boom to bust. Not surprisingly, anxiety pervades the drawings made during the war years. “It’s so monumental, it becomes like a Greek tragedy,” Philippou says. “And, like a Greek tragedy, it talks of all the things we can’t avoid: birth, life, death.”

Braverman, a writer and performer, shares his great uncle’s story in Wot? No Fish!!, which is about to begin a run at Battersea Arts Centre. Somewhere between a lecture and a performance, the show is delivered by Braverman himself, sifting through his surprising inheritance. Of the many questions the piece asks, Braverman highlights the way it prods at notions of high and low art. “What is the value of art in our lives?”

Philippou breaks in: “And who’s allowed to make it?” Both men describe the wage packets as an example of outsider art, but they are adamant that Ab is an artist by any standards. “Whenever anyone uses the word doodle I say no,” Philippou insists. “It is art, and it’s fantastic art.”

The outsider emerges as a recurrent theme of Ab’s art and of the show. As the son of Jewish immigrants, Ab was something of a marginal figure himself, with antisemitism casting a shadow over several of his drawings. In a Britain where immigration is once more the subject of fierce public debate, this is where the show’s subtle but insistent politics is located.

There is also, I suggest, a modern resonance to Ab’s compulsive sharing. What he depicted in art, we now publish on social media. In the same way that Ab’s drawings give equal space to death and trivia, as many Twitter posts are devoted to the serious as to the silly.

“It’s very different,” counters Philippou. “What you do in a tweet is you spend 10 seconds doing it; what you do with a work of art is you make it. You don’t make a tweet.” What has been lost, Philippou and Braverman suggest, is craft and care. “It does make you wonder about that mode of communicating – where is it now?” asks Braverman.

The answer, perhaps, is in the theatre. Wot? No Fish!! is not one but two stories, Braverman says. “There’s the story, and then there’s the story of the story. There’s the story Ab draws, but also the story of my discovery and my connectedness to it. It is about history in the present.”

“Somebody said the show is an act of love,” Philippou recalls. “I think that’s probably true, but it’s only true because Ab’s work was an act of love. The best way to love somebody is by not looking away. It’s continuing to look.”