How do you solve a problem like Beckett? Or maybe the question should be: how do you solve a problem like the Beckett Estate?

Since his death in 1989, Beckett’s plays have been vigilantly policed, with new interpreters required to be scrupulous in their following of the playwright’s detailed instructions. One example: in his excellent book Drama: Between Poetry and Performance (2010), W. B. Worthen cites a Performance Licence Rider from February 2000 attached to a licence to perform a number of Beckett’s short plays:

There shall be no additions, omissions, changes in the sex of the character as specified in the text, or alterations of any kind or nature in the manuscript or presentation of the Play as indicated in the acting edition supplied hereunder; without limiting the foregoing; all stage directions indicated therein shall be followed without any such additions, omissions, or alterations. No music, special effects, or other supplements shall be added to the presentation of the Play without prior written consent. (p.208)

That doesn’t leave much room for interpretation. There’s also a certain irony involved in the issuing of a rider like this. It is, in Worthen’s words, “writing meant to constrain the implementation of dramatic writing already said fully to constrain its proper use in the theatre” (p.208). The purpose of the Estate is to protect the authority of Beckett’s texts, yet the necessity of such protection points to a chink in that authority that Beckett’s gatekeepers would otherwise seek to deny. The authority of the theatre text is limited; to borrow a favourite phrase from Michael Goldman, performance always materialises something “in excess” of the words on the page, no matter how detailed those words might be.

But watching some Beckett productions, you’d be forgiven for missing that “excess” of theatricality. Perhaps out of fear of the Estate, perhaps out of reverence for the playwright, too often “new” versions of Beckett’s texts surrender to deadening fidelity. In trying to be slavishly loyal to authorial intention, theatre-makers rob the plays of what has made them enduringly brilliant. Beckett’s world is one of theatrical images that startle and bruise, not raise weary yawns of familiarity. When David Jays explains why he and Waiting for Godot have parted ways, I get it. As he puts it, new interpretations of plays should be about “creating acts of theatre rather than acts of worship”.

I’ll ‘fess up to a bias here. As a researcher, I have a fair amount of intellectual investment in the idea that text is not a prescriptive set of instructions for performance. But I don’t think I’m making a particularly controversial argument. As a director, Beckett himself made changes to his own works in performance, the cutting of the Auditor from Not I being perhaps the best known example. This suggests that he understood – in a way his Estate sometimes seems not to – that each new performance context shifts the relationship with the text. Without that understanding, we might as well banish Beckett’s work to the page, treating it as literature rather than material for performance. Too much reverence does neither playwright nor audience any favours. And it doesn’t exactly help to dispel the persistent idea that Beckett is hard work: impenetrable, fenced off and reserved for the faithful few.

The pretext for banging on about all of this is the Barbican’s International Beckett Season, which just came to a close over the weekend. As well as the Sydney Theatre Company production of Waiting for Godot that finally put an end to Jays’ long, ambivalent relationship with the play, the season offered a reading of the short story Lessness alongside new(ish) renditions of Not I, Footfalls, Rockaby, Rough for Theatre, Act Without Words II, Krapp’s Last Tape and All That Fall.

I caught the latter two on Friday night and was immediately struck by the contrast between them. They are, for a start, two very different pieces of writing, if both recognisably “Beckettian”. In each there’s the silence, the loss, the absences; the pairing of comedy and melancholy; the unrelenting fucking loneliness of being alive sometimes. But while Krapp’s Last Tape takes place in a gloomy, sealed-off space, its protagonist all alone in the darkness, All That Fall is a rich aural tapestry of rural Ireland, full of voices and landmarks.

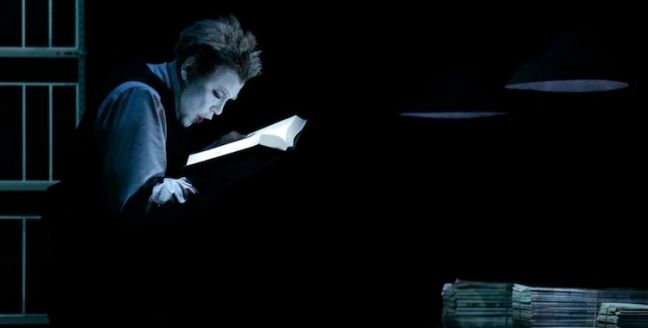

More than that, though, the productions from Robert Wilson and Pan Pan Theatre respectively have tackled the restrictions of staging Beckett in intriguingly different ways. Wilson’s production layers onto and stretches out Beckett’s structure, the essential shape of which is left (naturally) intact. The opening sequence, before Krapp begins listening to the voice of his younger self, becomes an extended prelude. Face white and hair on end, every feature down to his red socks evoking the clowns of silent cinema, Wilson stares out at the audience while a storm rages outside the box-lined walls of Krapp’s study, the sound almost deafening. It goes on. And on. When finally Krapp (past and present) begins to speak, the words are all carefully in order, but they’ve been given a strange, cartoonish gloss.

Wilson’s production is crisp, precise, consistent. The aesthetic, monochrome apart from that teasing glimpse of red, is part-comic strip, part-silent movie. The light is stark and exposing, in sharp contrast with the surrounding darkness – much like the juxtaposition between clowning comedy and gnawing despair. This is Krapp as deathly, fearful and purged of depths; a pale shell of a man, condemned to the folly of missed opportunities and playing to an audience long gone. Conceptually, it all adds up. But I don’t feel the play. Watching from my comfortable seat, the chill of loss and loneliness never touches me. By painting on top of what’s already there, Wilson’s version becomes all surface.

Pan Pan Theatre’s All That Fall, on the other hand, adds in order to strip away. Conceived for radio, Beckett famously said that the play was “written to come out of the dark”. Here, the darkness remains, but it’s given intermittent illumination. Rather than staging the play as such, Pan Pan Theatre have created an experience that attunes its audience’s attention. The Pit at the Barbican becomes a listening installation, a landscape of wooden rocking chairs, glowing lights and dangling bulbs. It is astonishingly beautiful, a cocoon of a place that I wish I could escape into every time I listen to radio drama.

Seated in our rocking chairs, we listen to the shifting voices and sounds of All That Fall with the delicate accompaniment of Aedín Cosgrove’s lighting design. Stripped of other visual references, our focus is directed in a way that it rarely is today when we listen to the radio (I’ve even taken to making myself close my eyes when listening to radio plays as a precaution against distractions). Unobtrusively evocative, the brightening and darkening of the lights, forming ever-changing patterns, subtly hints at the play’s narrative and themes, coaxing us into different emotional states as the journey of Maddy Rooney winds its melancholy way to the station and back. Even the gentle rocking movement of the chairs is in tune with the piece, the repetitive rhythm mapping onto the lilting Irish accents and the tides of loss, time and memory. It might no longer be a radio play in the precise way it was originally intended, but Pan Pan Theatre’s version feels in many ways like a purified, distilled experience of All That Fall.

My opening question is the wrong one to be asking, really. Plays aren’t problems to be solved; the very idea of a solution, with all the definitiveness implied, goes against the ever-shifting, ever-transforming nature of theatre texts. So does the iron rule of an Estate for whom honouring a text can only mean strictly obeying it down to the last letter (it’s possible even to ask what “obeying” really means when moving from one medium to another). To borrow once again from Worthen, texts written for performance are “designs for doing”. They beg for enactment, not exhumation.

Or, in short: Love Beckett. Hate the rules.

Top photo: Lucie Jansch.