This is the text of a provocation I delivered at the TaPRA Conference last week.

‘Are you ready?’

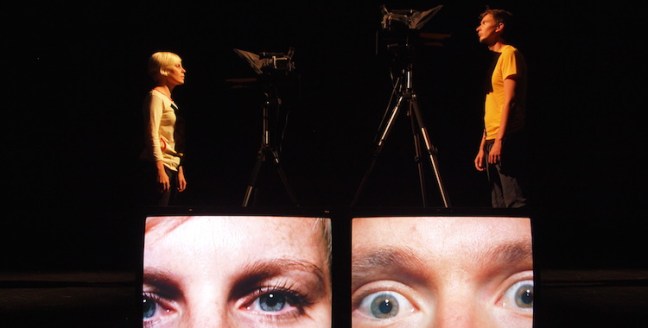

The three words that open Slap Talk, Action Hero’s durational slanging match, are a challenge to both audience and performer. Inspired by the pre-fight trash talk traded by boxers, and by the culture of 24-hour rolling news, the show pits performers Gemma Paintin and James Stenhouse against one another in a relentless battle of words, reading out a barrage of insults from a scrolling autocue while close-ups of their faces are live-streamed on two large screens facing the audience. The piece continues without pause for six hours, with audience members free to come and go at any time.

Throughout the performance, Paintin and Stenhouse are slaves to the text scrolling in front of them – which they have also written – yet the durational format stretches and unsettles the relationships between text, performer and spectator. Today, I want to begin asking how the durational dramaturgy of Slap Talk might emphasise the slippage between text and performance, in the process begging larger questions of the authority of the theatre text and revealing the everyday violence of language.

The violence of language is an ongoing concern in Action Hero’s work. In an interview, Stenhouse told me ‘we’ve been talking a lot about the tyranny of the script, and how in a more conventional theatre structure the script’s pre-written by someone and then they give it to a director and some actors and then they read it out and the audience watch it – what the power structures are within that.’ He later added that the company’s work is interested in ‘the ways in which iconography and image can occupy […] psychic territory, and how then that can dictate how you think and the words you say; how that’s a really violent act’. In another interview, and with specific reference to Slap Talk, Paintin said ‘We were interested in violence within language and how you can make anything sound violent if you wanted’.

In Slap Talk, language is twisted to harness the latent violence contained in multiple aspects of twenty-first-century society: capitalist economics, Hollywood movies, faceless bureaucracy, the dieting and wellbeing industry, government rhetoric, advertising speak. The list goes on. Initially, familiar statements are pushed to their extremes through an escalating game of one-upmanship. ‘I was born ready’ mutates into ‘I was ready before your parents parents parents even thought that they might have kids one day’. Increasingly audacious synonyms and inventive swearing likewise play a large part. Over time, though, anything and everything becomes an insult, from the diagnosis of a therapist to scenes from Apocalypse Now. Often, the language is reminiscent of the endless data stream of the internet, constantly spewing out facts and opinions and cat videos.

The volume and density of this relentless assault of information reflects what John Tomlinson calls the ‘condition of immediacy’: ‘a culture accustomed to rapid delivery, ubiquitous availability and the instant gratification of desires’. This is also a culture in which media and communications play an integral role in our everyday experience of the world; according to Tomlinson, we are now subject to ‘a distinct, historically unprecedented mode of telemediated cultural experience’. His theory responds to a common feeling that the pace of life in the twenty-first century is getting faster and faster; a side-effect of what David Harvey, at the end of the previous century, identified as ‘an intense phase of time-space compression’. New technologies have condensed both spatial and temporal distances, shifting the way we experience and think of time.

This brings me, then, to the significance of Slap Talk’s duration. Edward Scheer suggests that ‘the idea of duration has always been essential to the experience of performance’. Performance is a time-based art. One aspect of performance that is often seen as its defining feature is its liveness: it happens in a particular space and time, and therefore its duration is integral to its identity as performance. As Beth Hoffman puts it, ‘to be live is always to be live in time’.

Often, though, we take this time for granted. What certain live art, performance and theatre practices have done is render that time legible. Hans-Thies Lehmann identifies ‘new dramaturgies of time’, emerging around the 1960s, which ‘suspend the unity of time’ and create a ‘new concept of shared time’ – that is, time shared by both audience and performers. By distorting time, often through durational practices, artists concentrate our awareness on its passing and on the different ways in which it is experienced.

Action Hero achieve this both through Slap Talk’s six-hour running time and through the many slippages made apparent in the performance. The live-streamed close-ups of Paintin and Stenhouse’s faces, for example, split and double their performances, nodding to the role of televisual media in our speeded-up society and drawing attention to the simultaneity of bodies and filmed images. This once again recalls Lehmann, who argues that ‘through the uncertainty of whether an image, sound or video is produced live or reproduced with a time delay, it becomes clear that time is “out of joint” here, always “jumping” between heteronomic spaces of time’. Elsewhere, Paintin and Stenhouse make direct reference to both the duration of the performance and the disjuncture between subjective time and clock time, for example in this exchange about how long they have left:

How long’s left?

About 2 hours

Have you got a clock on your side?

No

How do you know it’s 2 hours left then?

It just told me

What?

It just told me there’s 2 hours left

How do you know it’s telling the truth?

What do you mean?

I mean what if it just said that to make you feel better, maybe there’s actually hours left and its just a mind trick.

Some of the most interesting moments in Slap Talk, meanwhile, are the sequences in which Paintin and Stenhouse appear to go off script, digressing briefly from the deluge of insults to reflect on what they’re saying. ‘That’s too far,’ interjects one performer after the line ‘I’m gonna pour bleach down your throat’, raising the question of where we draw the line in our representations of violence. The rebuke comes a few moments later: ‘I’m just saying what it tells me to say!’

As the piece goes on, though, it becomes clear that even these interruptions are tightly scripted. Take this exchange, which occurs towards the end of the piece.

You know anyone could do what you do, you’re just a puppet. Someone’s telling you what to say.

That’s not true.

It is true.

No it’s not, I say whatever I want to say.

No you don’t, you say what you’re told, because that way you keep everyone’s attention. Everyone looking at you, and you’re telling us you’re going to look after us and meanwhile all hell is breaking loose behind your back, and you’re just a mouthpiece.

That’s not true, I say what I want to say.

That’s bullshit. They’re making you say it!

No.

They’re doing it right now.

Here, and in the lines that follow, Action Hero play with multiple layers of meaning-making, pointing to their roles as both writers and performers and playing with the ways in which text does and does not dictate performance. For Paintin and Stenhouse, their interest in text is ‘fuelled by the ways in which language exists in the live space’. By making the text a visible presence in the form of the autocue and by exerting pressure on the text-performance relationship by elongating the duration of the piece, they repeatedly draw attention to this role that language plays in live performance.

And by placing pressure on the performance text, Action Hero also place pressure on the everyday violence it enacts, the scripting of theatre becoming an implicit analogy for the ways in which various power structures aggressively script our speech. In Slap Talk, language games stretch meaning until it is emptied; initially violent metaphors become tired and ridiculous. Carl Lavery argues that ‘in their exhaustion of the signifier, that supposed token of human mastery, language appears meaningless, hollow, its affective charge dispersed. […] Gemma and James open up the possibility of living differently, of allowing violence to be avoided because it has been expressed, allowed into consciousness – exhausted.’

In speaking about time and durational performance, I’m very aware of my own limited time, which is fast running out. I’ll try, then, to get to the point as quickly as possible. According to Hoffman, ‘time-based art’s task […] is to (re)imagine multiple principles of coherence and connectivity in order to provide an account of the relationship between the movement of time and the experience of meaning-making’. We tend to think of durational performance as revealing something about time and our experience of it; as making an intervention in our accelerating twenty-first century lives. And Slap Talk certainly does this, both replicating and stretching beyond endurance our speeded-up culture of constant information.

But I wonder if durational dramaturgies such as Action Hero’s might also offer an intriguing challenge to how we conceive of the relationship between text and performance. Slap Talk stages the ‘tyranny of the script’, to borrow Stenhouse’s phrase, but also its limits. As time wears on and exhaustion affects Paintin and Stenhouse’s performances, mistakes are made and unexpected moments disrupt the text. As spectators, we can be less and less sure if those apparent slippages are scripted or ad libbed. And because the text is present in the space, we become sharply aware of its role in that relationship between ‘the movement of time and the experience of meaning-making’, perhaps reflecting on how text functions in other performances.

Lavery describes Action Hero’s dramaturgy as ‘a dramaturgy of quotation’. They situate genres, images, gestures and speech acts in new contexts, demonstrating Derrida’s insight that citation always changes that which is cited: ‘Iteration alters, something new takes place’. By placing this particular text – or collection of texts – within a durational performance context, Action Hero alert us not only to the multiple rhythms of time, but to the functioning of text in performance and simultaneously of language in society. Might, then, the durational dramaturgy of simultaneity and slippages explored in Slap Talk productively disrupt the authority of the text in performance?

—

References:

Action Hero, Action Plans: Selected Performance Pieces (London: Oberon Books, 2015)

Derrida, Jacques, Limited Inc (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1988)

Harvey, David, The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change (Oxford: Blackwell, 1992)

Hoffman, Beth, ‘The Time of Live Art’, in Deirdre Heddon and Jennie Klein (eds.), Histories and Practices of Live Art (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), pp.37-64

Lavery, Carl, ‘Introduction’, in Action Hero, Action Plans: Selected Performance Pieces (London: Oberon Books, 2015), pp.vi-xxiv

Lehmann, Hans-Thies, Postdramatic Theatre, trans. by Karen Jürs-Munby (London and New York: Routledge, 2006)

Scheer, Edward, ‘Introduction: The end of spatiality or the meaning of duration’, Performance Research: A Journal of the Performing Arts, 17.5 (2012), 1-3

Tomlinson, John, The Culture of Speed: The Coming of Immediacy (London: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2007)