Originally written for Exeunt.

Back in 2009, Andy Field wrote a piece on the Guardian Theatre Blog with the bold and frankly brilliant title ‘All theatre is devised and text-based’. His argument, essentially, was that theatre is theatre is theatre. As he explains, “To devise is simply to invent”, making distinctions between devised and text-based theatre ultimately meaningless. Whether something is brought into being based on a set of instructions or a collectively built model that is constructed in a rehearsal room, in the end it’s all just inventing.

It’s extraordinary to look back on this now and realise that Field’s argument was being made so persuasively four years ago, and yet the debate continues to rumble on. Only last month, I attended a conference at Reading University at which an entire heated session – prompted by a provocation from David Edgar that was certainly provocative – revolved around the binary that Field effortlessly dissolves. As blindingly obvious as Field’s breakdown of this dichotomy might seem, the institutional structures supporting British theatre, from development programmes to universities to theatre critics, perpetuate the cleaving of work into these two misleading categories.

Duska Radosavljevic’s refreshing new book, therefore, is more necessary than a glance at Field’s blog might suggest. Theatre-Making lays out its most important intervention in its very title: Radosavljevic proposes this term as the foundation of a new vocabulary for discussing contemporary theatre, bringing it all under the inclusive umbrella of making. While the context of current binaries is acknowledged with frequent reference to genealogies, the book is persuasive in arguing why they are now outdated, with the actual work that is being made often defying the restrictive terms in which it is discussed.

Radosavljevic makes the case for transcending existing binaries by documenting a range of different contemporary practices that challenge the straightforward categories of devised and text-based. The book moves through the staging of Shakespeare, processes of devising and adaptation, new writing, verbatim theatre and relational practices, demonstrating in turn how each of these different practices bridges the gap between devising and playwriting, as well as inviting audiences into a kind of co-authoring. Examples range from the Royal Shakespeare Company to Tim Crouch, from Simon Stephens to Ontroerend Goed.

As well as making the case for doing away with the devised/text-based binary more clearly and succinctly than any other text I’ve read on the subject, Radosavljevic adopts a striking and perhaps telling approach to the supporting criticism she draws on. While it is not uncommon to see newspaper critics referenced in academic texts on theatre, thus far the new forms of criticism that are evolving online have been largely ignored. It’s intriguing, therefore, to see an almost perfect balance in Theatre-Making between print and online writers – if anything, that balance is tipped slightly towards the latter.

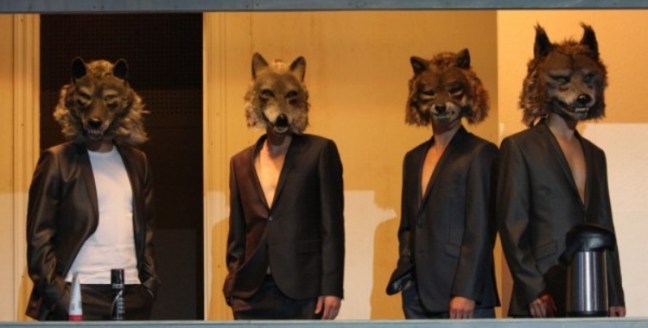

This shift is highlighted in a section on Three Kingdoms, which is the production to provoke perhaps the most vociferous online reaction to date. After considering the critical debate at length, Radosavljevic concludes that “the most important outcome of the controversy around the Three Kingdoms reception […] was the way in which the blogosphere managed to outweigh the mainstream press in the depth of insight and its intellectual enquiry”. While this is one very specific example, it suggests that the potential for a new vocabulary of the kind advocated by Radosavljevic might lie in new forms of criticism rather than in the mainstream theatre press.

Having traversed a wide variety of contemporary theatre-making practices, Radosavljevic eventually concludes that these works, “emerging through the encounter between theatre and performance-making strategies”, represent a convergence of what Patrice Pavis defines as “text” and “mise-en-scene”. The implication of this convergence is that it “finally makes it possible for the text to be understood as one element of the theatre or performance-making idiom, thus transcending previously entrenched hierarchies”.

In light of developments that just happened to coincide with my reading of the book, Radosavljevic’s observations and suggestions seem to be vindicated at every turn. Returning again to Field, Forest Fringe (which he co-directs) have recently published the second issue of Paper Stages, described by them as “a festival of performance contained within the pages of a beautifully designed book”. This is not a blueprint for a performance event, but an event made into paper, ink and imagination.

This project demonstrates a deliberately playful approach to the text, with a gleeful lack of regard for the categories it has previously found itself forced into; Paper Stages is neither script nor record, but a set of suggestions for performance – even the word instructions feels too prescriptive. The book is what its reader makes of it, requiring them to reconfigure their own understanding of the relationship between text and performance.

Around the same time, I was also intrigued to see that Bryony Kimmings had published a script of Credible Likeable Superstar Role Model to coincide with the show’s run at the Soho Theatre. This is the culmination of a conversation between Kimmings and publisher Oberon that started last year, when Kimmings began to wonder how her work might take textual form. Would it be a kind of documentation, or a set of instructions that might allow others to reconstruct her shows? I have yet to see a copy of Credible Likeable Superstar Role Modelmyself, but I understand that large chunks of it take the form of poetic descriptions of the onstage action, acting not as stage directions, but also not quite as a straightforward record.

These are just two examples that spring immediately to mind. Everywhere artists are subverting restrictive and prescriptive understandings of the theatre text, but many of the structures around them remain out of step. The hope is that, following Radosavljevic, our critical vocabulary might begin to catch up.